Why (co)designers need a scope of practice

by KA McKercher | First published December 2023

TLDR: (Co)designers can benefit from creating a scope of practice to communicate our skills and limits to the people we work with and for. A scope of practice can help us be accountable, say no, grow our skills and notice where we could and should partner with others who know things we don't.

I teach and support designers and co-design facilitators to develop and use a scope of practice to work responsibly. I share my experience and template here.

Understanding (co)design as an unlicensed profession

(co)design is a largely unlicensed profession (except architecture). So, unlike licensed professionals (such as Australian Health Practitioners or UK Health & Care Professions), (co)designers don’t have to:

meet registration standards

maintain our competency

commit to reflective practice

work to a defined code of ethics

receive regular supervision and more

The people who work with us (as clients, co-designers, participants or something else) can’t easily access information about our skills or ethics either. How do they know what to expect? How can they seek accountability for ineffective, demeaning or dangerous design practices?

This article isn’t about debating whether design or co-design should be licensed [1] or how we choose the designers we need, but shares some initial thoughts in draft about what scope of practice might mean for designers.

Experience tells me there are risks for everyone involved when designers haven't thought about and don't share their scope of practice. So, how do we minimise those risks and work more skillfully?

While the harm might be minimal when a designer exaggerates their skill in visual design, the consequences can be severe when designers claim to be competent in co-designing with made-vulnerable populations or don't realise we've walked into a specialist skill (such as working with conflict or with kids, safely). Unconscious incompetence is dangerous for everyone involved.

Turning care back on ourselves

I'm noticing increasing expectations on designers (and other workers) to share their lived experiences at work, often without talking to each other. We are not entitled to all parts of each other. If we’re to share our lived/living experience in doing/leading projects we need to be asked and may need support.

There are lived experiences I share openly in my work and others I don’t because they’re too wobbly. I worry about transferring my woundedness to others [1]. Past me naively worked in spaces that brought up repressed memories and destabilised me significantly. I can't effectively hold myself or others in those spaces. They are outside my scope of practice.

Exploring scope of practice as designers

The UK Health & Care Professions Council [3] describe scope of practice as:

“…the limit of your knowledge, skills and experience and is made up of the activities you carry out within your professional role.”

In design (including leading co-design) I take this to mean:

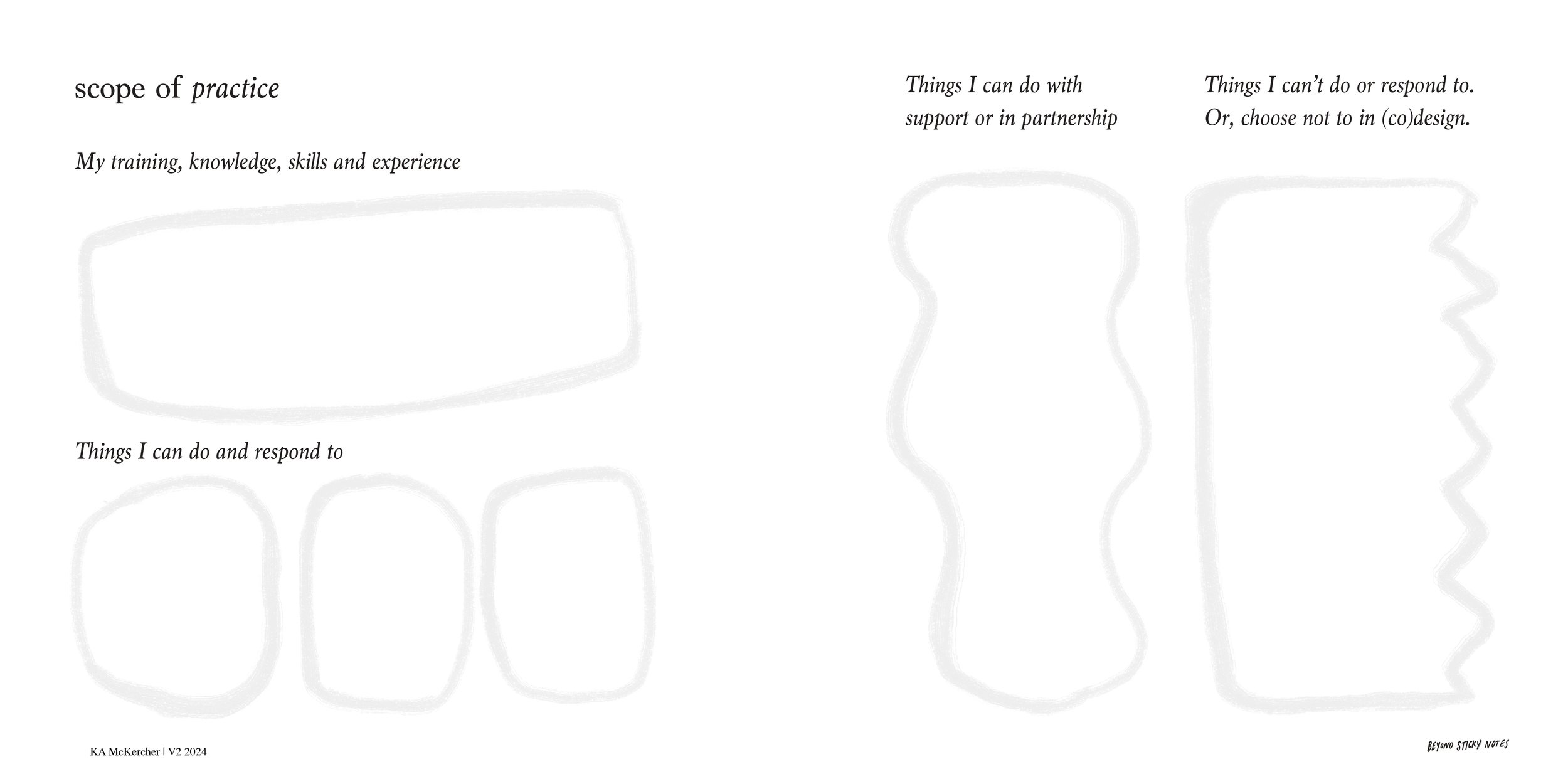

What we know how to do. Our knowledge, skills and experience gained through our lived and living experience(s), cultural knowledge, education, paid and unpaid work, mentoring, coaching, supervision and from other places.

What we don’t do (and others know we don’t do). Our honesty with ourselves and others about what we aren’t skilled to do or respond to, for example, managing serious disclosures, doing conflict resolution, mediation or offering therapy. And the parts of ourselves we keep for ourselves.

How we keep growing and practising accountability. The ways we thoughtfully maintain our skills, reflect on our practice individually and with others and how we grow new skills when the work demands it.

Where we partner to extend our scope of practice. We cannot know all things. In my work, I often partner to expand my scope of practice; for example, I don't specialise in co-designing with kids or young people, but together with colleagues who do we can work competently.

Trying it yourself

I invite you to develop a scope of practice for yourself.

Like a template? Here’s one you can try. Hate templates? Do it your way. You’ll find some examples on page two from my 2023 scope of practice.

Please know:

You can learn and grow.

You might be uncomfortable or resistant to thinking about your scope of practice. That's normal. What might that discomfort mean?

You might say no to work because of your scope of practice. And others might say no to you. That can be a positive outcome, especially if it means harm reduction for all involved.

Your organisation isn't entitled to all parts of you.

Sharing your scope of practice can enable conversations, growth and accountability. Not sharing it may result in the opposite.

💌 Invitation: If you'd like paid support developing your scope of practice individually or as a team contact us at hello@beyondstickynotes.com.

⛔ Boundary: Please don't send us detailed disclosures of harm you've experienced as a designer working outside your scope of practice, or by designers. We're not resourced to work with those disclosures.

[1] You might like to check out these resources and conversations exploring designing as an unlicensed profession:

Listen to: Rachael Dietkus, LCSW , Morgan Cataldo Tad Hirsch and I explore 'Practicing without a license' in conversation on This is HCD

Read: Tad Hirsch's paper Practicing Without a License: Design Research as Psychotherapy (2020)

[2] Finding our Way (Podcast) 2023 A Radical Anger with Lama Rod Owens.

[3] UK Health & Care Professionals Council. Scope of practice.